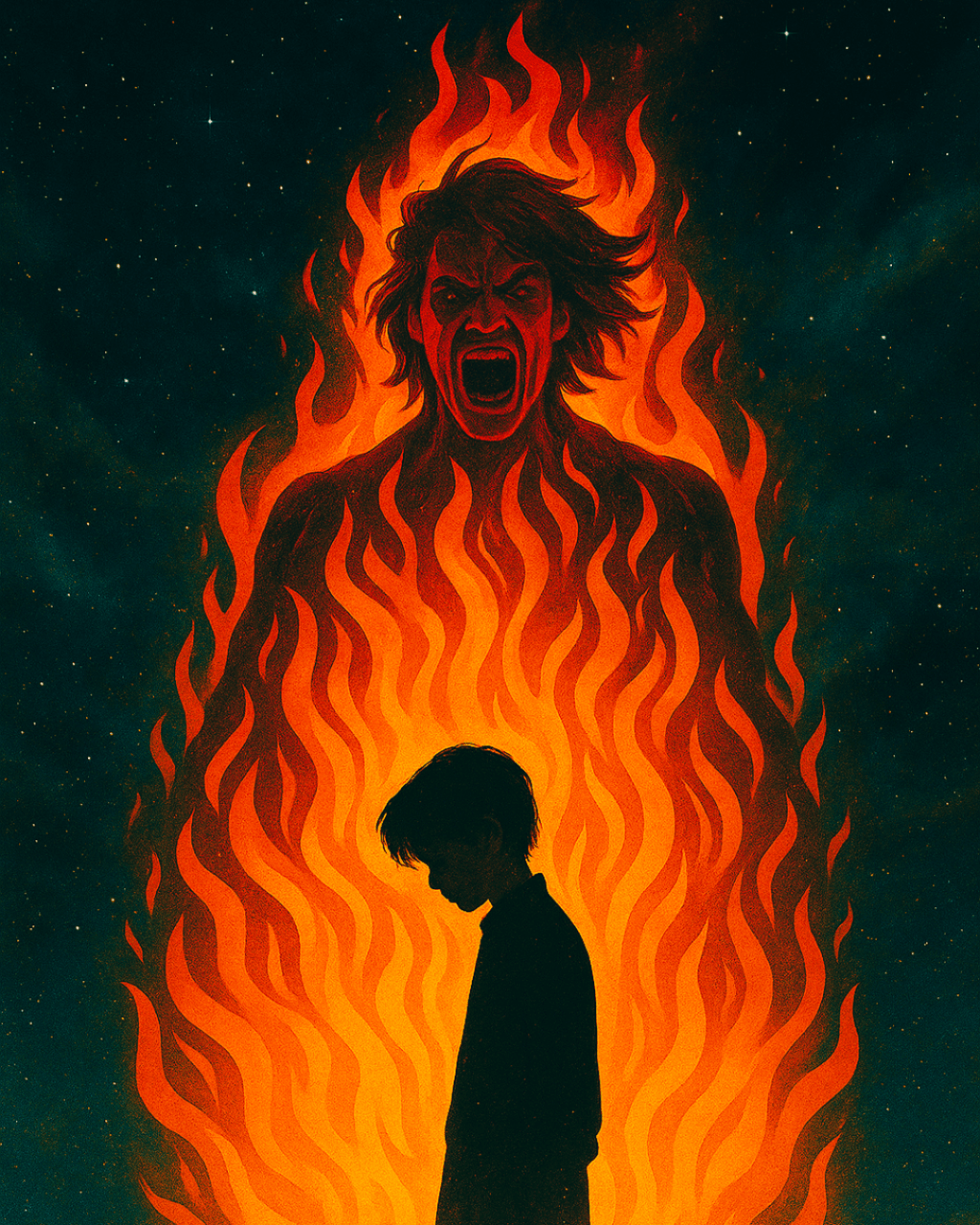

As far as I can tell, the greatest tragedies are not born from rage.

They are born from grief that has nowhere to go—and the fear of facing it.

Revenge of the Sith isn’t just a sci-fi blockbuster.

It’s a tragedy of Shakespearean depth.

It is one of my personal favorites and it is arguably George Lucas’ magnum opus—the full flowering of every mythic, emotional, philosophical instinct he had been building toward across decades.

We tell the story of Anakin Skywalker’s fall as if power itself were the poison that unmade him.

But beneath the lightsabers and battles, it’s something quieter and infinitely more human:

A boy who never stood a chance.

Grief left unspoken festers.

Fear mutates into violence.

Hope falls into ruin.

And this pattern is older than any galaxy far, far away.

When we mourn the past more than we imagine the future, we doom both.

If Revenge of the Sith feels familiar, it’s because we’ve heard this music before.

There was once a prince who could not save his father;

And once a knight who could not save his love.

One saw a kingdom rot from within;

One saw a Republic burn from without.

One chose the sword too late;

The other chose it too soon.

Both lost everything they fought to keep.

Both became the ruin they were meant to stop.

Revenge of the Sith is Hamlet, rewritten in flames.

It’s the story of how a wound left untreated can hollow out an empire.

First performed in 1600, Shakespeare’s Hamlet traced the slow collapse of a soul unable to survive its own sorrow.

Four centuries later, George Lucas—shaped by the study of tone poetry and mythic design—wove a tragedy that rhymed in fire.

To Lucas, stories were felt—tone poems in light and breath.

Like Hamlet, Anakin was destroyed by love twisted into fear—by grief he was never taught how to carry.

And when that grief became unbearable, he did what the wounded so often do:

He mistook possession for salvation.

He reached for control and called it power.

And in his terror, he destroyed the very thing he sought to save.

Padmé did not die because fate demanded it.

She died because Anakin could not let her live.

And the galaxy watched a menace rise—

born from the broken heart of a boy too wounded for words.

Anakin’s greatest fear was detachment—the slow unmooring of everything he loved.

From the moment he was born into chains, life taught him that nothing could be trusted to stay.

Not family.

Not freedom.

Not even love.

The Jedi asked him to sever this fear, to bury it beneath discipline.

But Anakin could not.

He clung to Padmé out of terror—

the terror that love was a mirage, that every hand he reached for would eventually slip away.

In trying to conquer detachment, he made his losses complete.

It began a long time ago—with a boy who learned too soon that survival demanded sacrifice.

And that love was always a risk he could not afford.

When Anakin lost his mother, he lost the last of his unguarded trust.

Fear filled the hollow space where innocence had once lived.

So when he became Vader, his first act was not conquest.

It was the destruction of innocence—the silencing of the part of himself that still remembered what it was to be pure.

Hope, he had been taught, was a weakness.

Innocence was a liability.

And in that terrible act, he finished the work that life had started:

He killed the boy who might have been saved.

Anakin Skywalker was not defeated by weakness.

He was brilliant.

He was strong.

He was gifted beyond imagining.

But brilliance cannot carry grief.

Strength cannot silence fear.

And so, in the end, it was not his enemies who defeated him.

It was the ghost that lived inside his own chest—

the terror of loss, the dread of detachment—

that hollowed him from within.

By the time Anakin let Mace Windu fall to Palpatine’s hand, his fate was already sealed.

The Jedi had not betrayed him.

Padmé had not betrayed him.

Even Obi-Wan, with all his sadness and caution, had not betrayed him.

Anakin betrayed himself.

He could not wait.

He could not trust.

He could not believe that grief could be borne without conquest.

When Obi-Wan called out, “Palpatine is evil!”

the obviousness of it almost rang with bitter comedy.

Of course Anakin knew.

But by then, Anakin is no longer choosing between good and evil.

He is choosing between a future he can control—and one he cannot.

And in that desperation, he has already lost the plot.

On the black shores of Mustafar, Obi-Wan stood above him and said:

“It’s over, Anakin. I have the high ground.”

But by then, the high ground was no longer physical.

Obi-Wan had already surrendered to grief.

He had mourned his master.

He had mourned the Republic.

He had learned how to carry sorrow without letting it devour him.

Anakin could not.

He still believed he could leap across the chasm inside himself—

that with enough force, he could defeat grief, defeat loss, defeat fate itself.

He leapt.

But grief is heavier than gravity.

And so the body fell because the soul already had.

When Anakin struck at Obi-Wan, he was not just defying a master.

He was defying the nature of mourning itself.

And it cost him everything.

Fear hardened into rage.

And rage burned the future to ash.

The Jedi taught Anakin how to fight.

How to serve.

How to obey.

But no one taught him how to grieve.

No one taught him how to love something deeply—

and still let it pass beyond his reach.

No one told him that love survives death.

And so, despite all his brilliance, despite all his strength, Anakin could not master the one thing that mattered most:

how to let go without destroying what he loved.

Because as far as I can tell, the tragedy was never that Anakin Skywalker fell.

It’s that no one ever taught him how to catch himself without breaking the world.

Leave a comment